March 2013. It was that time of the year again – the spring slowly receding to give way to the advancing heat of the Delhi summer. If I did not make my foray into Rajasthan now, then I would have to wait till the monsoons had gone. After testing the waters with a short venture to Jaipur the last year, I was now ready to take a bigger leap, and naturally, that leap would have to land me in Udaipur, the city of lakes, that I had heard so much about – Chittorgarh, that famed land of brave hearts, would be a nice addition.

On 29th March 2013, just like on my previous trip to Rajasthan, I boarded an ordinary road transport bus to Jaipur after office from Iffco Chowk in Gurgaon. Listening to one studio album after another, each from start to finish, of my favorite band Michael Learns to Rock, I reached Jaipur around 10 PM. After a quick dinner and some inquiring, I got on a private operator’s bus headed to Udaipur – in hindsight, I should have taken a state transport bus only, for the seat was uncomfortable, with pathetic headroom. I remember getting woken up more than a couple of times due to bumping my head into the hardwood baggage shelf above, leading me to some soreness on my scalp.

I remember the bus passing through Bhilwara in the middle of the night when I was yanked out of my sleep, and as the dawn descended, the bus cutting through mist that shrouded the less-than-usual vegetation and isolated huts and houses sprinkled across the landscape in an envelope of haze. The next time I opened by eyes, I was informed by the bus conductor that the railway station had come – that was my cue to get down. Soon, just walking a few steps on the road running parallel to the railway station, I checked in to a hotel. Not wasting too much time, upon advice of the receptionist, I booked a cab to take me around Udaipur for about 1400 rupees.

Seeing Udaipur and Nearabouts

We started by heading off to the outskirts of the city, to the Eklingji temple located at Nagda, the first capital of Mewar, 25 km away from Udaipur. The original temple dedicated to Eklingji, the ruling god of the Mewar princely state, was built by Bappa Rawal, the founder of the Guhila Rajput dynasty, who established the Mewar kingdom in the 8th century AD. The temple underwent cycles of destruction by Turkic forces and re-construction, most notably in 14th century by Rana Hammir, the progenitor of the Sisodia clan to which Maharana Pratap belonged, and in 15th century by Rana Kumbha. The last major re-building with installation of the current idol was done in late 15th century by Kumbha’s son, Rana Raimal, after the temple had been devastated by the Malwa Sultanate forces.

After offering my prayers in the temple, we drove through a valley in the hills, which I was told were the Aravallis, that seemed largely yellow but splattered with patches of green. After about another half-hour of driving through alternating patches of flat land, clusters of hamlets, flanked by the Aravallis, we reached the Chetak Samadhi, built at the location where as per legend, Maharana Pratap’s horse Chetak breathed its last after taking its master to safety in the Battle of Haldighati against Akbar’s forces on 18th June 1576. Just another kilometer further, the road cuts through a narrow pass in the hill whose sides are barren and coloured pitch yellow with an orange tinge – the is the legendary Haldighati Pass, located at around a distance of 44 km from Udaipur.

Retreating from the Haldighati Pass, near the Chetak Smarak, I checked out the Maharana Pratap Museum that depicts the life and times, the exploits and achievements of Maharana Pratap. Maharana Pratap, the eldest son of Udai Singh II who founded Udaipur, was crowned in Gogunda as the 54th ruler of Mewar in 1572, inheriting a kingdom that had been weakened by the 1567-1568 siege of Chittorgarh. His refusal to form an alliance with and become a vassal of the Mughals and conitnued conflicts with the latter led to the legendary Battle of Haldighati on 18th June 1576, which the Mughals won although they could not capture Maharana Pratp or his close family members.

Forced to flee to safety of the hills with a trusted coterie of warriors and loyalists, amidst annexation after annexation of most key areas of Mewar including Gogunda, Udaipur, Kumbhalgarh etc., Maharana Pratap led sustained attacks using guerilla tactics against the Mughal forces, and won back major chunks of Mewar, with an exception being Chittorgarh, leading to Mewar’s revival by 1588 AD. Celebrated as a folk hero in Rajasthan, Maharana Pratap’s legend later spread to Bengal where he became a symbol of resistance for anti-British revolutionaries, leading to him becoming a leading icon of heroism, alongside the likes of Rani Laxmi Bai, in India’s freedom struggle.

Again driving through the Aravallis, we re-entered Udaipur city, where I straightaway where we first stopped by the Fateh Sagar lake, and then proceeded to the City Palace where I dismissed the cab. The construction of City Palace on the bank of Pichola lake commenced in 1559 AD, when Rana Udai Singh II moved his capital from Chittorgarh to Udaipur on the advice of a hermit, much before the siege of Chittorgarh by Akbar in 1567-68. Successive rulers of Mewar, including Maharana Pratap and Maharana Amar Singh I, occupied palace adding more layers to it. The palace complex, built entirely in granite and marble, comprises components such as courtyards, palaces and balconies, with intricate mirror work, murals, marble work etc. are a fine representative of Rajput architecture.

Taking in the grandeur and aesthetics inside the City Palace, coupled with amazing views of the Pichola Lake with the Aravallis in the background and the city, I exited the City Palace to directly walk into the Jagdish temple. Built by Maharana Jagat Singh in 1651, where Lord Jagannathi in the form of an idol carved out of a single black stone is worshipped, the temple is a fine example of Māru-Gurjara architecture. Spending some more time by Pichola lake, and admiring the spots of illumination emanation out of the Lake Palace (Jag Niwas) and Jagmandir Palace lying in the middle of the lake, I walked through the streets and then the main roads back to my hotel near the railway station, following a day well spent.

Chittorgarh

The next day I pondered over two options – to go to Kumbhalgarh or to Chittorgarh. At that point in time, I knew only of Chittorgarh, being enamored by sketches of a tower called Vijaya Stambh that appeared in an issue of Tinkle magazine. Perhaps at the same time in the same magazine or later, I had read about the legend of Panna Dai, who replaced the prince with her own son when the prince’s uncle attacked. Later came the story of queen Padmini. With the image of the Vijaya Stambha and the name Chittor stuck in my head for so many years, and the prospect of seeing the Vijaya Stambha for real knocking at my doors, it was rather easy to choose which place to go to.

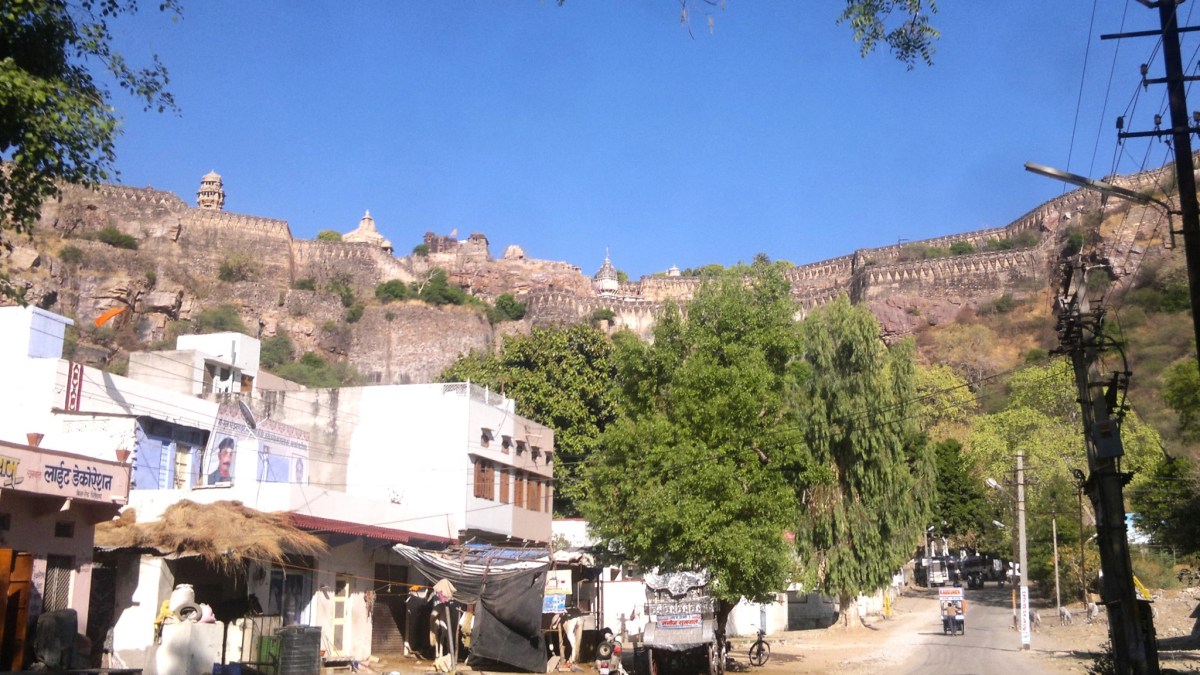

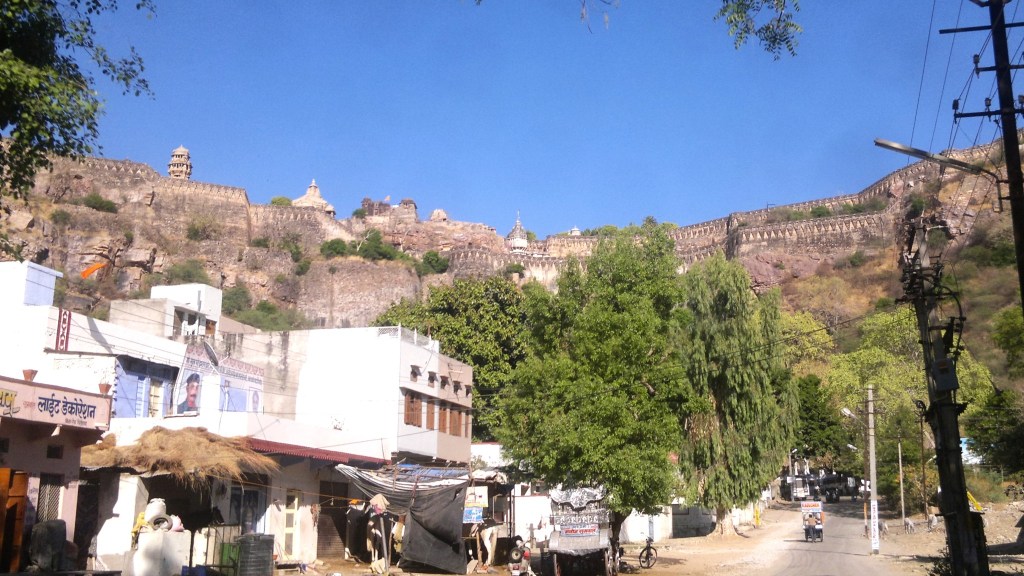

By 9 AM next morning, I was in a state transport bus headed to Chittorgarh, which I reached by 11 AM. There, I hired the services of a middle-aged autorickshaw driver who doubled up as my guide for tour of Chittorgarh fort – the package costing me 500 rupees. Right from where we started, I could see the fort wall streaming up and down over the rugged edge of the hill in the distance. As we drew closer and closer to the hill above which the fort lay, I saw the outline of several structures jutting out into the sky – a narrow vertical structure stood taller than the others, and I wondered aloud if that was the Vijaya Stambha, to which my guide replied, yes.

Soon, the autorickshaw was clattering up the winding road, passing through multiple stone arched gates, called pols, one after another. At long last, passing through a cluster of normal but old looking houses, looking very similar to a village, we came on to an open clearing on flat around where the ticket counter stood. Buying my ticket, we rode further on the road towards the south until we reached a crossroads with multiple structures occupying the space on all sides of the crossroads. A palace stood right beside me, which I learnt was Kumbha’s palace. A cluster of marble built Jain temples stood on my left side, while two stone-built Hindu temples stood diagonally opposite side.

I got down at the crossroads to first see Kumbha’s palace, and then proceeded a little to the south to see the aforementioned two temples, namely, Kumbhashyam temple and Meera temple, the latter being a Krishna temple where Meera Bai from Merta who had married into Chittor, immersed herself in devotion to Krishna. Back outside the temple complex, as I turned my gaze a little to the south-west, I saw that right in front of me at a distance stood a tower that looked eerily similar to the one I remembered from the sketch from the magazine – it was indeed the Vijaya Stambha. Without further ado, I beckoned my guide to head straight to the Vijaya Stambha.

Reaching the foot of the Vijaya Stambha, I beheld the physicality, the carvings and the design of the structure with glee and wonder that would only be elicited in a child that has finally seen something that it had seen in a dream or on TV. The Vijaya Stambha was built in 1488 by Rana Kumbha to commemorate his victory over the forces of Malwa in the Battle of Sarangpur. Dedicated to the god Vishnu, it is said to be visible from anywhere inside the fort, and also from the city. What is more – it was possible to climb up the tower using the staircase located inside the structure, which is what I did with sheer excitement. Reaching the topmost of the 9 storeys, I got a breathtaking view of the city underneath and other structures inside the fort on the hill.

Getting down from the tower, I proceeded from beside the Jauhar place to Samadhishwara temple, which houses a three-faced Shiva idol. Behind the temple is the iconic water tank appearing in most circulated posters of Chittorgarh. Descending the steps I went to a crevice in the hillside from where emanates a water spring from an stone opening built in the form of a cow’s (Gau) head (mukh) filling up the water tank, thereby giving it the name Gaumukh Kund. From there, I got back on the autorickshaw and moved further south past a water tank to reach the Kalika Mata temple. Then further to the south, I stopped by the Padmini Palace, where a legend, albeit with no historical backing, of Ala-ud-din Khalji getting a glimpse of queen Padmini through the reflection on a mirror, is rooted in.

Pushing further south, the road curved around a water tank with a deer park occupying the outer side, and turned 180 degrees towards the north, with thin jungle flanking on both sides. Now heading a couple of hundred metres, we came upon the main gate of the fort, which overlooked the sparsely inhabited valley below. A stony curving path led from the valley below to the gate, with a low flat hill stretching from one end to another in the background, while ramparts streamed along the edge of hill from both sides of the gate. Moving further to the north, we came upon a cluster of Jain temples, amidst which stood another tower, looking like a prototype of the Vijaya Stambha, called Kirti Stambha, which is dedicated to Adinatha and was built in the 12th century.

Pushing further north for another kilometer or so, we reached the north end of the hill, where a full fledged village is located. Again turning a full 180 degrees, we were headed in the south direction again, first passing through the village and then, meeting the road by which we had first entered the village on our way up to the fort. As we rolled down the hill through the numerous gates on the winding road, I looked wistfully at the ramparts above me, a little dismayed that I had to say goodbye to the place that I had been fascinated with for so long. As we stumbled back into the city at the foothill, I took one last glance at the hillside that wore the the stone ramparts as a crown and supplemented it with structures as if bedecked with gems.

It was 5 PM when I took a road transport bus back to Udaipur. After a quick dinner, I boarded a pre-booked 9.30 PM bus to Delhi, and fell asleep, only waking up when the bus arrived in Dhaula Kuan in Delhi the next morning.

Post-script

In the end, what struck me most after visiting Chittorgarh is how it is a self-contained city spread upon a vast flattop hill, like on a plateau. The palaces and structures are far-flung interspersed with water tanks and jungle. If you’ve read The Lost World, then imagine a place that is removed from the remaining world that lies beneath, and one that transports you to another era as a time machine. All said and done, Chittorgarh, a place I had loved since I was a child, since before I even set foot in Rajasthan, turned out to be place that lived up to and went beyond the hype and visuals I had created in my mind.