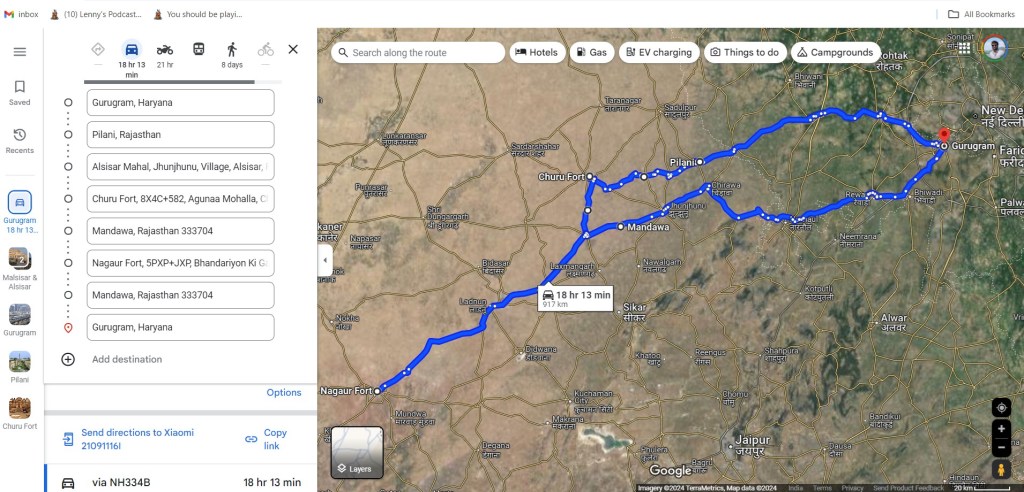

In my search for places that could be visited on a single day trip from Gurugram, Khetri seemed to pop up on a few occasions. I did try to plan a Khetri trip a few times over the last three years, even attempting to rope in my colleagues once, but it was not to be, especially since it would need a detour from all the major roads. I also abolished thoughts of doing a solo drive to Khetri because I was uncertain about the condition of roads and the remoteness I would encounter.

That was until the time my parents were here in Gurugram, and we really had to find something for a day trip before they returned to Odisha. While mother is always excited for any arbitrary new place, father only agreed once I brought to the fore the connection of Khetri with Swami Vivekananda. So, off we started on a mid-December morning around 10 AM in the quest to uncover Khetri.

We first drove towards and bypassed Rewari, then took NH 11 – that runs westwards to Jaisalmer through Jhunjunu – till Singhana, and then turned to the left, passing first by a low stretch of the Aravalli, and then approaching a pass in a cluster of the low Aravalli hills. Soon we were flanked by the Aravallis on both the sides, as we drove up the road winding through the pass, and finally reached a wide patch of undulating land surrounded by the Aravallis, with low houses and buildings sprawling across the dry valley, and swarming with people betraying a certain laid-backness in their demeanour.

It already being 1.30 PM, we asked around for a good place to have lunch, and took a hairpin upturned bend from the main road, reaching a haveli that once belonged to the royal dynasty. Now turned into Hotel Haridiya Heritage, the haveli is located higher than most of the town, affording a view of the erstwhile king’s palace which lies almost adjacent to it, and a view of the Aravallis running on the other side of the town. Photographs and souvenirs from the past adorn the walls of the main hall transporting one to a more circumspect time, convincing us that the haveli would be a good retreat for someone looking to spend time in Khetri.

Our next stop following lunch was the royal palace which has since been given over to the Ramakrishna Mission who now run the mission in part of the palace. The remaining part has been turned into the Ajit-Vivek museum dedicated to displaying the life and teachings of Swami Vivekananda. But why is this quaint little town nestled in the Aravallis being spoken of in the same breath as a monk from Bengal, a land in the east of India? Well, this seems like a good point to take a detour and learn about the connection between Khetri and Swami Vivekananda.

Khetri and Swami Vivekananda

After starting his life as a wandering monk in 1888, Swami Vivekanand first set foot in Khetri in June 1891, meeting Ajit Singh, the ruler of the Shekhawat estate (thikana) of Khetri. Following a discussion on a wide range of subjects, Ajit Singh invited Vivekananda for dinner. Vivekananda ended up staying in Khetri from 4 June 1891 to 27 October 1891, during which period Ajit Singh taught Vivekananda to wear a turban in the Rajasthani style to protect him from the hot wind blowing in the area. With variations added of his own, Vivekananda made the turban a staple of his life, as evident from most of the well-known pictures of the monk. A teacher-disciple relationship and a life-long friendship had begun.

Vivekananda visited and stayed in Khetri a second time from 21 April 1893 to 10 May 1893. Learning of his wish to participate in the Parliament of World’s Religions as a speaker, Ajit Singh readily provided him with financial aid, and the tickets for the voyage, even escorting him till Jaipur, from whereon Ajit Singh’s Munshi escorted Vivekananda till Bombay. Purportedly upon Ajit Singh’s request, the monk also assumed the monastic name Vivekananda replacing his then-assumed name Vividishananda. The two remained in correspondence during Vivekananda’s stay in the west, with Ajit Singh providing him financial support whenever required.

Vivekananda visited Khetri a third and final time in 1897, upon Ajit Singh’s invitation, where he gave a lecture attended by Ajit Singh and many Eurpoean guests. During this visit, Vivekananda openly expressed his gratitude to Ajit Singh for his support. In 1898, Vivekananda requested that a monthly stipend given by Ajit Singh to his mother, be made permanent even after Vivekananda’s death. Ajit Singh honoured this arrangement, without publicising this, till his death in 1901 due to a collapse of a tower he was standing on, at the age of 39. Incidentally, Swami Vivekananda also died at the age of 39, the following year.

In 1958, Ajit Singh’s grandson, Bahadur Sardar Singh donated the then abandoned and dilapidated Palace of Khetri to the Ramakrishna Mission, who cleared and restored one part of the palace to establish a mission. Later, another part of the building, Fateh Vilas, was turned into a museum showing Vivekanda’s life and teachings, while also honouring Ajit Singh. The room overlooking the town and the Aravallis, where Vivekananda lived during his stays in Khetri has now been turned into a prayer room. Some letters of correspondence between Vivekananda and Ajit Singh are also on display.

*************

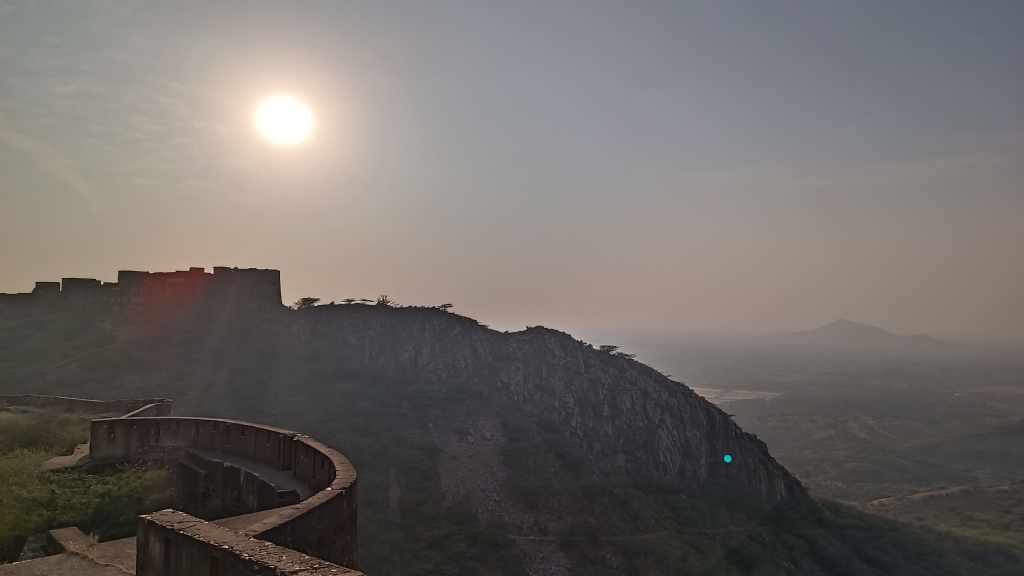

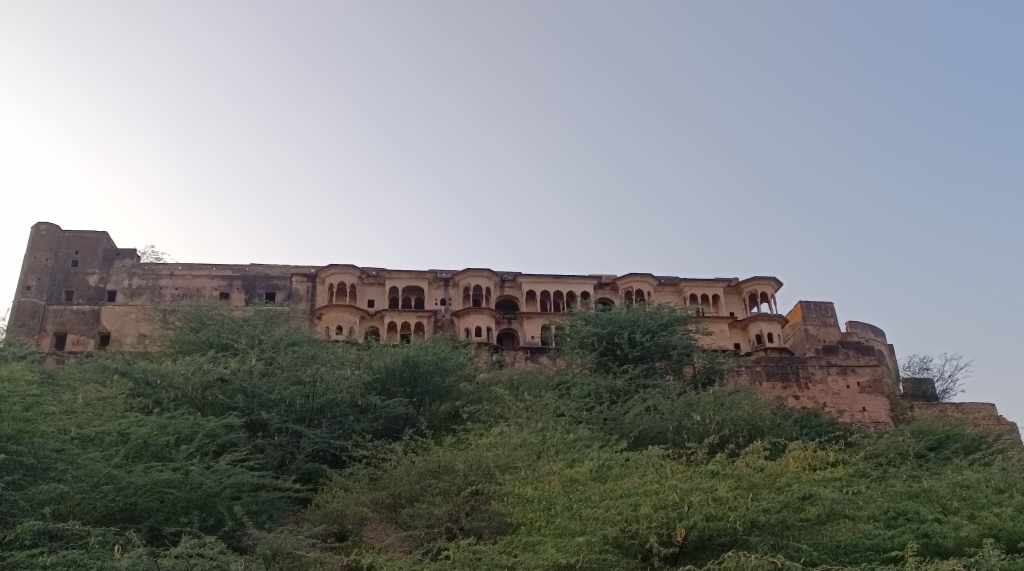

Offering our prayers in the prayer room, we then proceeded to the 270 year-old Bhopalgarh fort that beckoned us from the hilltop in the distance. Taking a steep two-kilometre winding road we were at the fort’s gate around 3.30 PM, with the Khetri town visible down below. Entering the fort premises, we immediately got a bearing of the area – the fort wall encloses an area shaped like a trapezoid, with most of the inner part depressed, resembling a wide crater.

Half a kilometre to the right of the entrance, bang on the fort wall is a palace sporting multiple windows and balconies, called the Sheesh Mahal, which is currently closed for renovation. Peeking in from the corridor at the main gateway, one could see a large courtyard and multiple storied halls and rooms surrounding the hall. Walking beyond the palace on the fort wall, one gets a clearer view of the Khetri town and the surroundings, including some now-defunct copper mines, nestled in the Aravallis.

From the side of the entrance and the walls stretching on both sides of the entrance, one can clearly see the Moti Mahal, an elongated palace, located at the far opposite side of the fort. In between, in the depressed portion, lay swathes of low jungle with vestiges of more stone structures. I traversed through the jungle by foot, and found the Moti Mahal in a desolate condition with the front of the palace overgrown with thorny bush and jungle, making it look like a prohibited place. However, adjoining the Moti Mahal, is located the Gopinath temple, dedicated to Krishna, with an attached dharamsala, teeming with some people, which made the adjunct palace look less hostile.

All this while, with my mind constantly racing about whether or not to enter the Moti Mahal, I kept lingering on the outside of the palace. It already being 4.30PM, with the prospect of darkness descending soon, I decided to take the plunge. With my heart in my mouth, wading through the thorny bush and jungle, I somehow managed to gain access into the palace, and was at first greeted by what looked like the king’s throne where he gave audience to the court. Walking through labyrinthine corridors and staircases, I managed to get access to the roof of the palace, from where I was treated to breathtaking views of the Shekhawat countryside chequered with low hills, and arid plains.

Around 5 PM, I descended from the roof of the Moti Mahal, intending to head back, and promptly lost my way through the labyrinthine corridors! After fumbling about in the low light, forced to use my mobile phone as a torch, for about 5 minutes, I was finally relieved to see that the exit had been present right before my very eyes – in my nervousness, I had simply not seen it! Exiting, I walked as fast as I could through the jungle to reach the fort’s entrance where my parents were waiting.

As we drove back through Khetri town, we looked with fondness at the agglomeration of houses straddling the valley in the Aravallis. Here was a town that retained the charm and compactness of a British-era princely state, and yet was no stranger to modern flourishes. It was easy to see why the monk Vivekananda would have appreciated the coziness of this town ensconced in the Aravallis, spending here 3 months at a stretch. Surely we could come back to spend 3 weeks at the least, we concurred amongst ourselves.