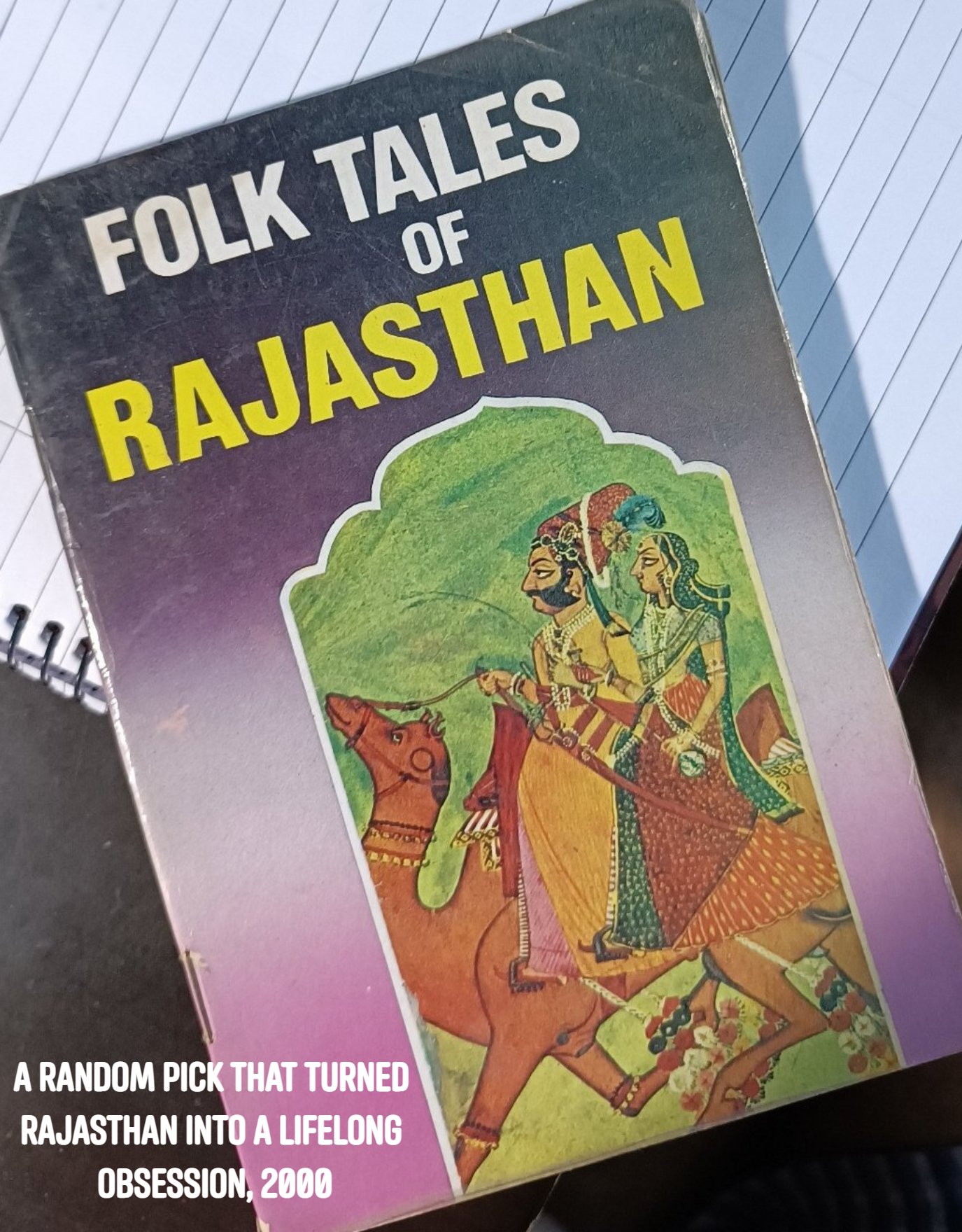

In October, during a brief illness, I got hooked on a book I had picked up in Udaipur in 2019 – Rajasthan: An Oral History, written by Rustom Bharucha, based on his conversations with the late Komal Kothari. Komal Kothari, who spent most of his prime documenting the folk music instruments, oral traditions and puppetry of Rajasthan, was instrumental in popularizing Managaniyar and Langa musicianship globally.

Komal Kothari’s insights into the relationship of the Rajasthani populace with their geography, natural elements, especially the arid stretches, their folk deities and folk traditions, as well as the intriguing interrelations amongst the various Rajasthani communities, left me in a trance. It was as if dormant connections to a distant past of mine were suddenly awakened. Besides, Komal Kothari lived in Jodhpur.

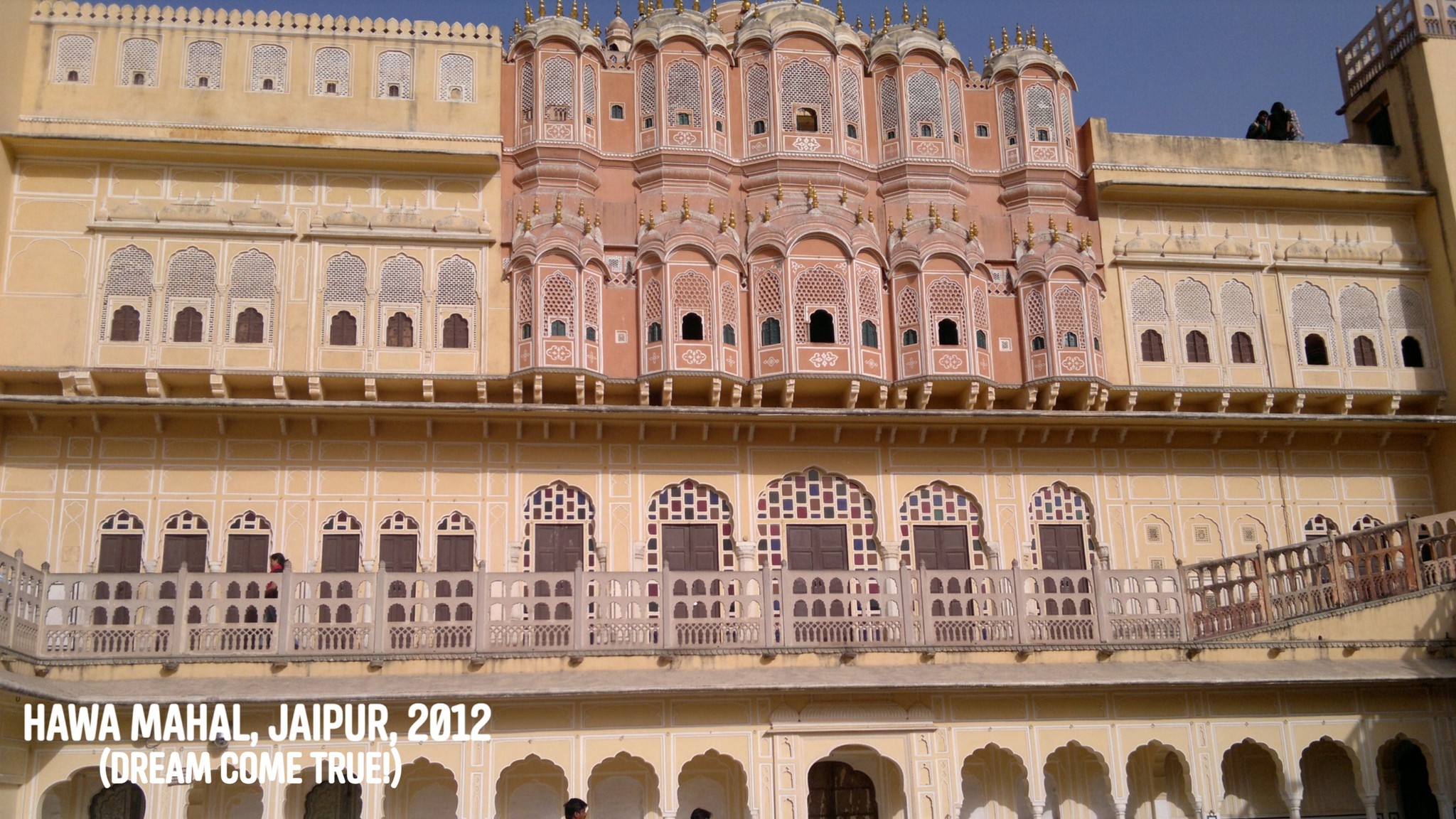

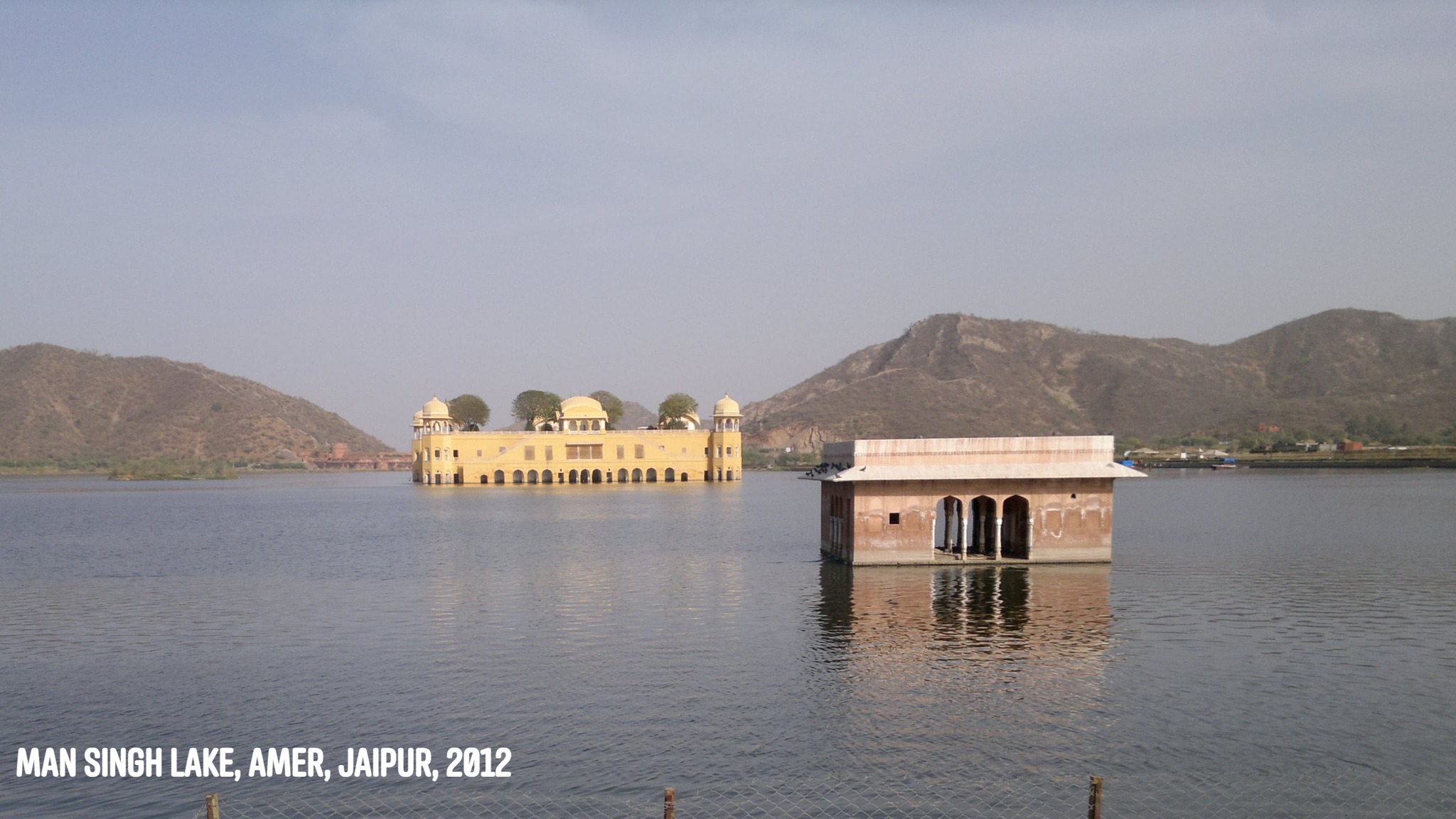

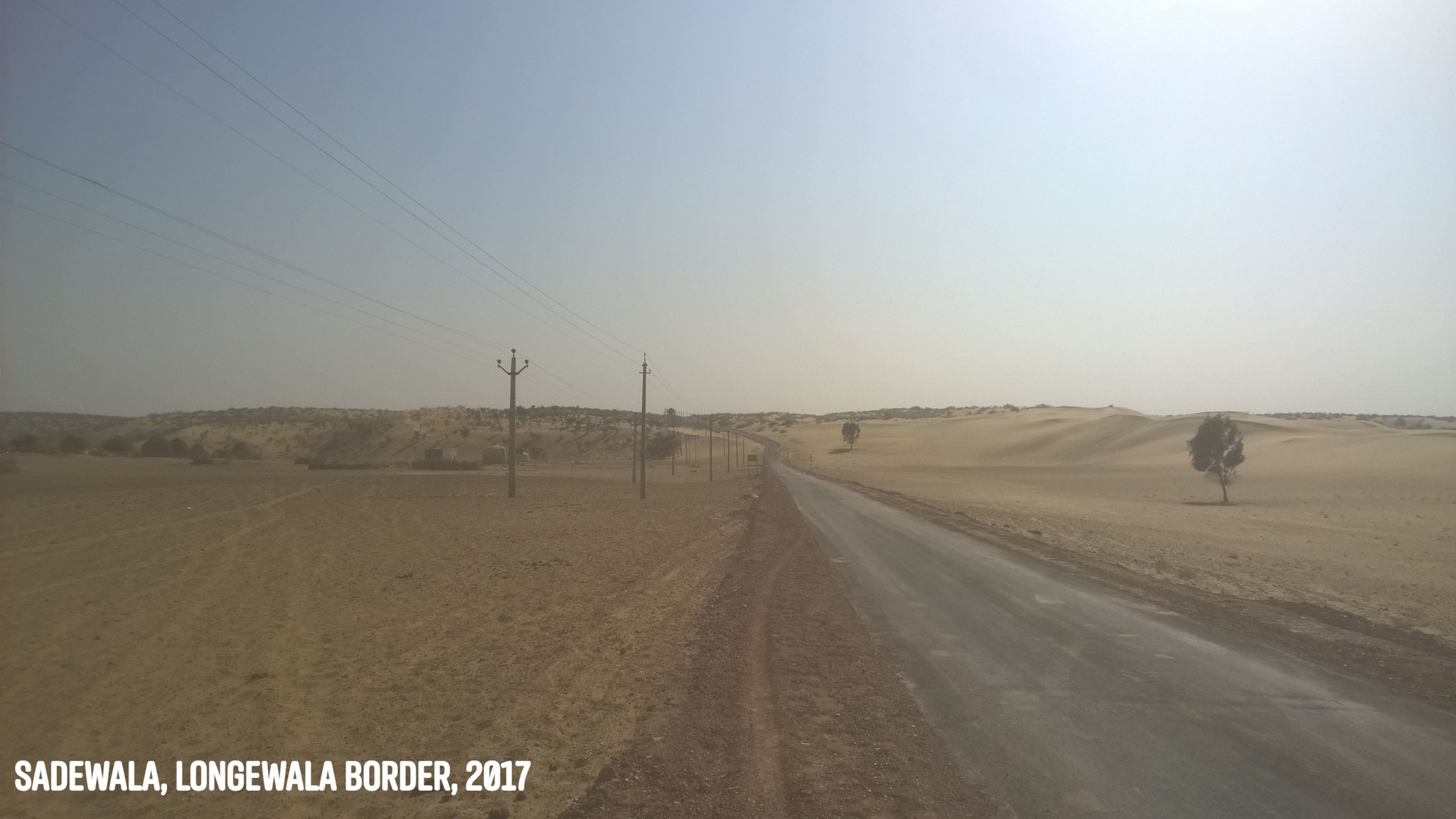

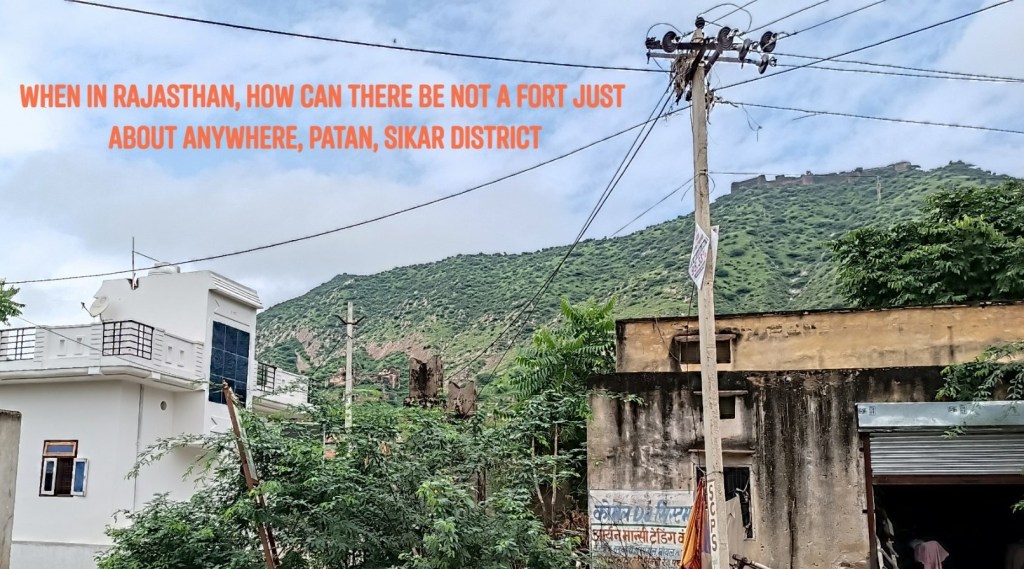

Now, since my 2019 outing to the Thar, Jodhpur had remained crouching in a corner of my mind. Mentions of Jodhpur anywhere, be it on social media, or television, or cinema, or by a friend, would stir long-repressed longings to go back to the city cradled in swathes of red-coloured escarpments. In two previous outings, everything that had to be seen in Jodhpur was already done and dusted with. Or, was it?

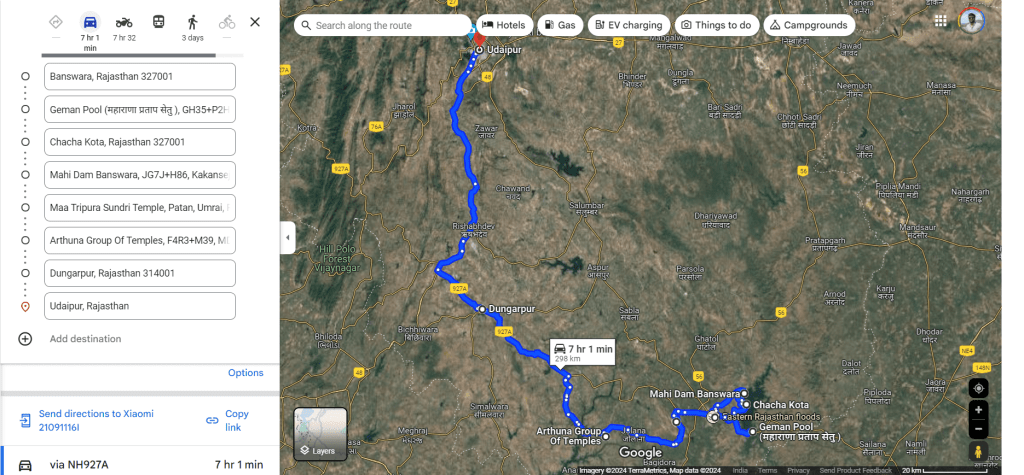

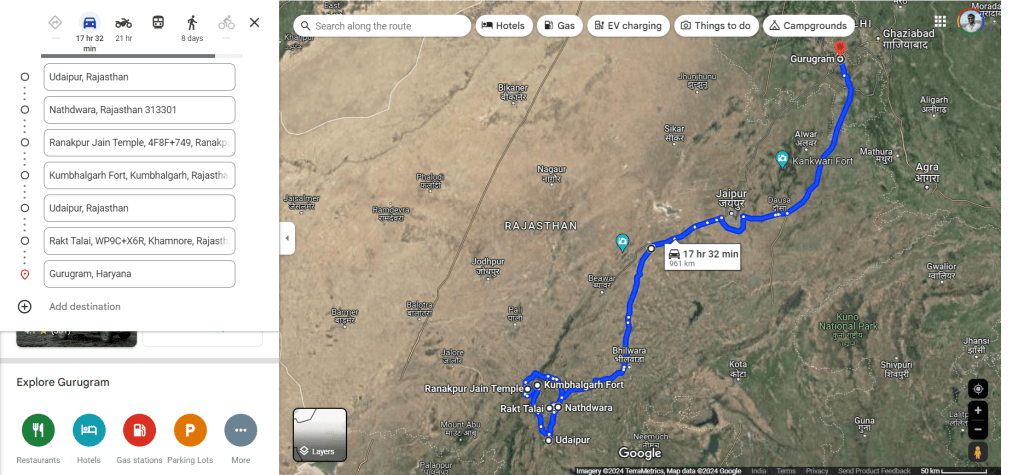

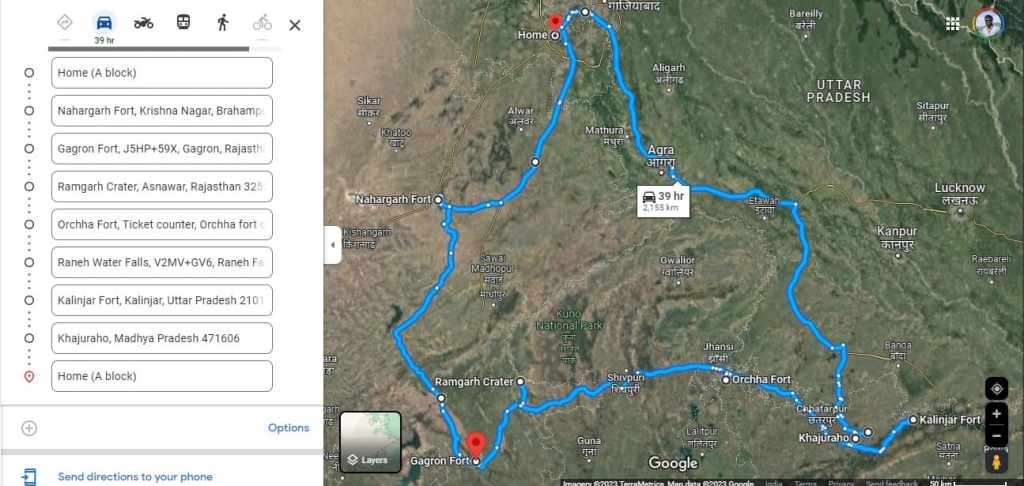

Nevertheless, in mid-November, my parents and I set off on our first-ever self-drive trip to Jodhpur via Salasar and Nagaur. What would follow was a spree of educational experiences: two involving things I had discovered about Jodhpur since our last outing, spurred somewhat by my reading during the intervening pandemic. And, a third we would just stumble into, and be pleasantly surprised by, despite my initial reluctance to indulge it.

A Living Museum

In an abandoned rock mine, on the low hill ranges encircling the western outskirts of Jodhpur, now covered with a blanket of grass and shrub, punctuated with the inimitable trio of ker, sangri and kumat trees, is located a unique interpretation of a museum. Arna Jharna Desert Musuem, literally meaning ‘forest and spring’, was the brainchild of Komal Kothari, who envisaged it as a showcase for the daily life of the regular desert folk.

The museum began with a single concept of displaying an object that is inseparable from daily life across all communities – the broom. On display in a cluster of huts are many more elements of daily life – pottery, utensils, storage spaces, cooking apparatus. Also on display are aspects of folk culture and indigenous knowledge systems. For instance, a humongous collection of musical instruments used across Rajasthan curated by Komal Kothari himself through his lifetime.

The most intriguing exhibit is a contraption serving as a portable shrine, called the kavad. A cupboard-like structure with multiple folds that can be progressively unfurled to reveal layers of shelves, it houses deities and pictorial depictions of religious stories and epics. The shrine moves from one place to another, accompanied by the storyteller, invariably from the bhat community, where he would narrate stories of the gods, folk-gods or epics to the patrons. Oftentimes, in the past, the patron would have a hereditary relationship with the bhat.

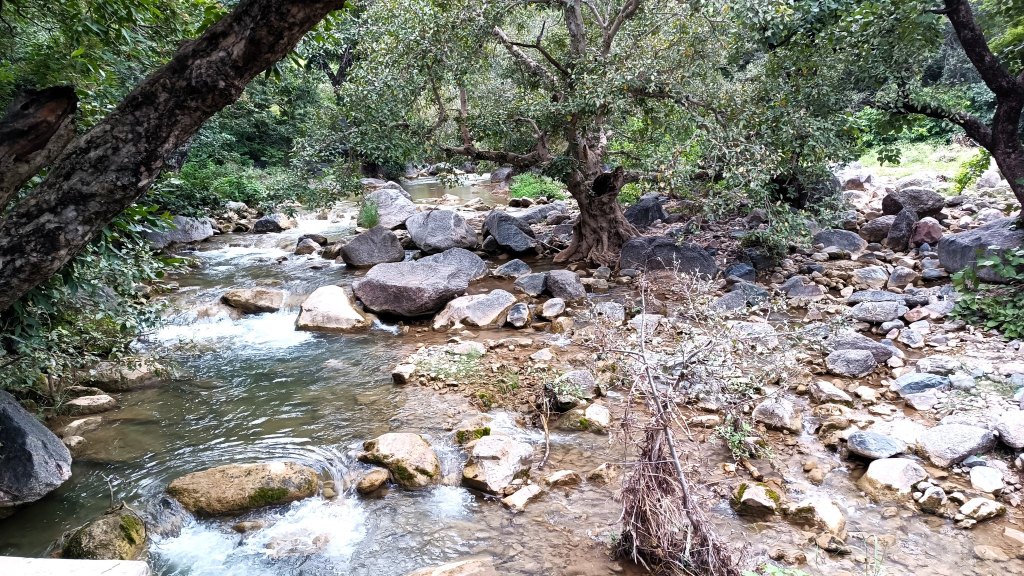

Walk towards the rear of the cluster of huts through the tall grass, and you reach the edge of a ravine with a stream that turns into a waterfall when it rains. The set-up of the huts in a cluster in a vastly open space reflects the general pattern of how habitation exists in and around the desert. The museum is highly recommended if one is keen for a glimpse into daily life in the desert, and into how daily life practices and processes have evolved within the ecological constraints of the desert.

A Nature Park

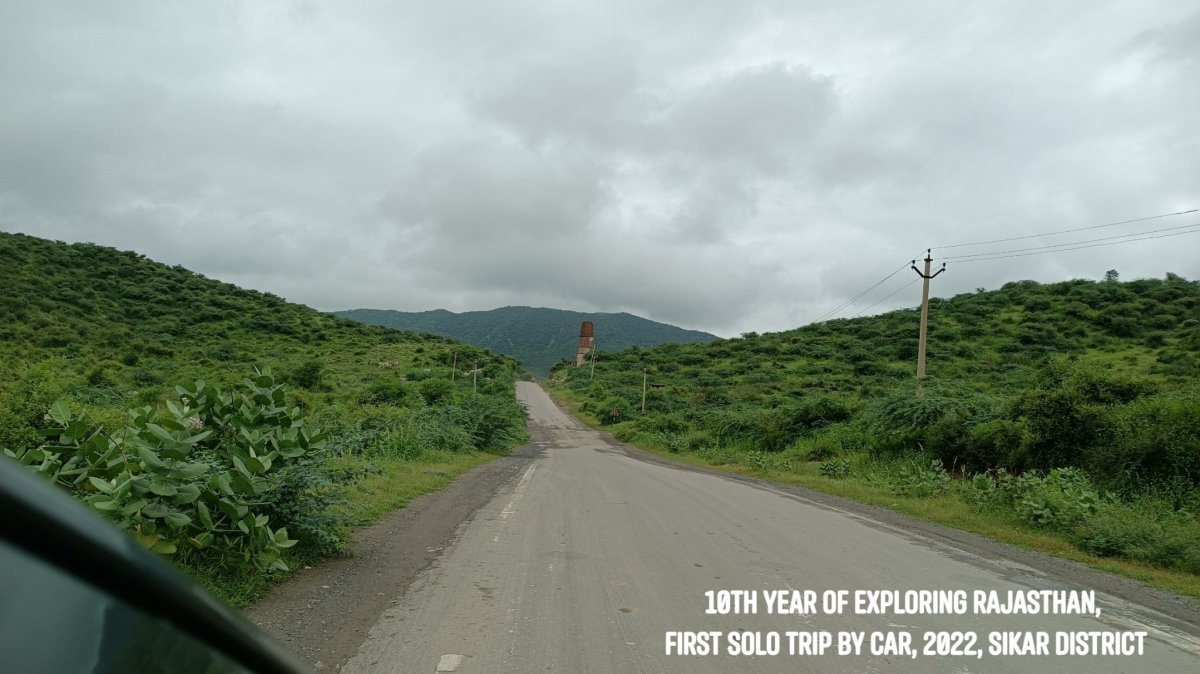

During the pandemic, I came across an interesting essay titled ‘Dying to Live’ in an anthology called Journeys through Rajasthan. Penned by the filmmaker-turned-naturalist, Pradip Krishen, it chronicles how a rocky desert landscape overrun by an invasive species mesquite (Prosopis Juliflora), colloquially called ‘bawlia’, was painstakingly transformed into a desert rock park through rewilding with desert-native plant species.

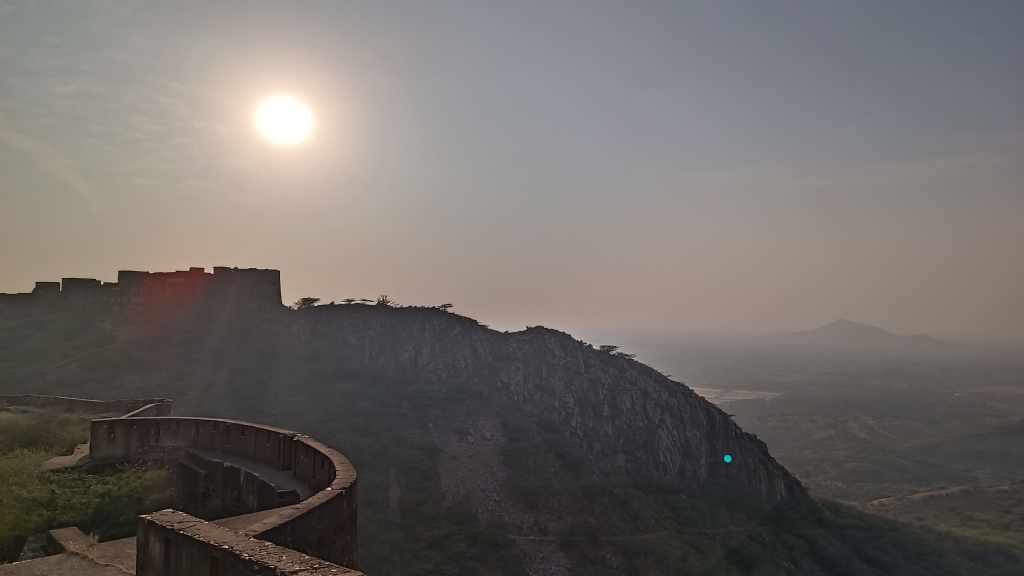

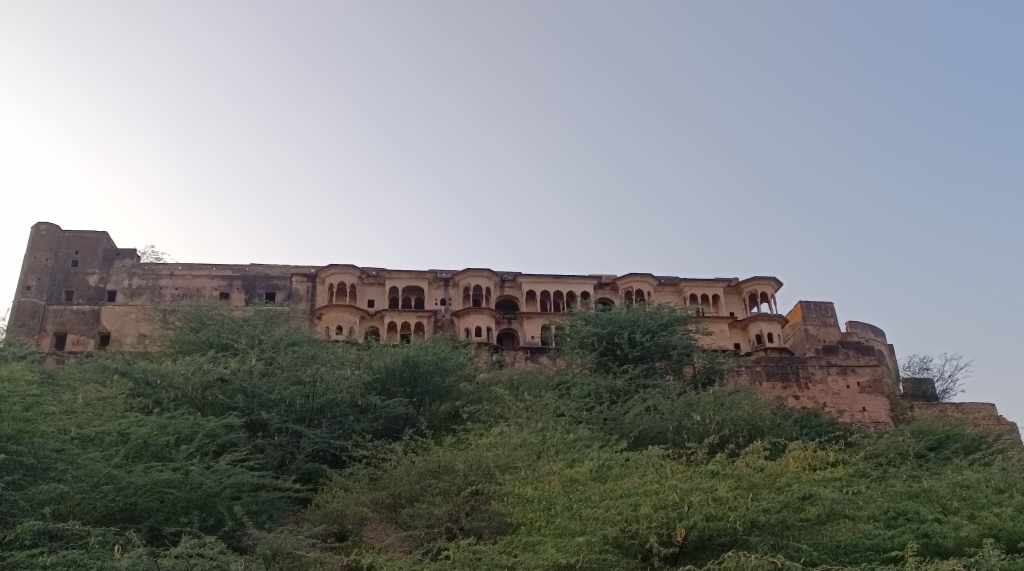

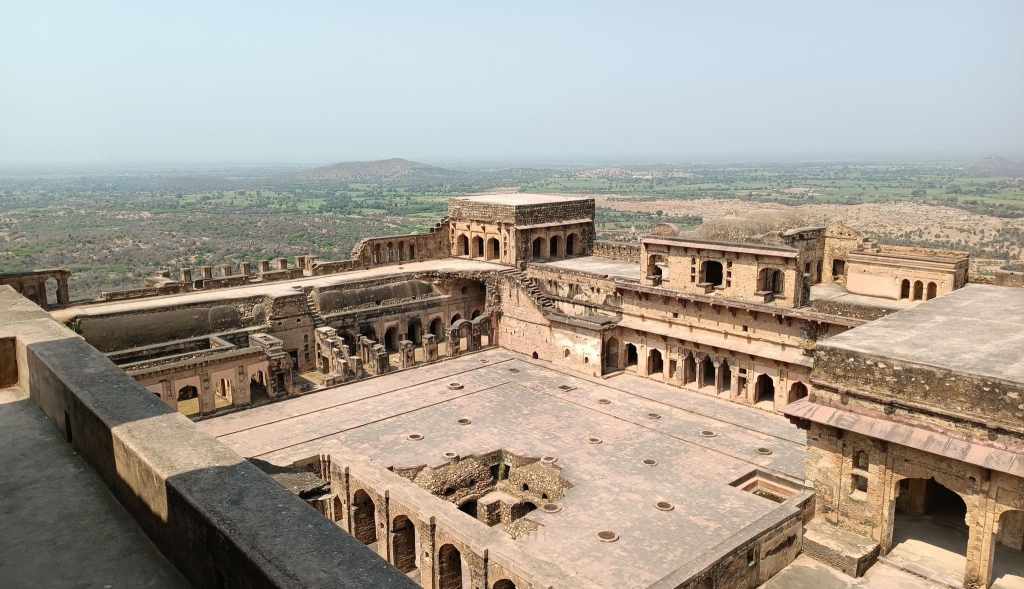

In fact, I had often wondered what lay behind the rocky outcrop holding up the Mehrangarh fort, and it turned out, it was this very park, the Rao Jodha Desert Rock Park. On our 2019 Jodhpur trip, we had even driven past the park on our way to Jaisalmer, but I had little idea back then that it was anything remarkable. Not until I learnt that the area in and around Mehrangarh fort was the site of not one, but two Geological Monuments of India – Jodhpur Group–Malani Igneous Suite Contact and Welded Tuff.

The Malani Igneous Suite consists of a variety of rock formations which resulted from a volcanic event occurring 750 million years ago. However, one variety of orange-pink coloured flat-faced columnar rock formations called rhyolite, is remarkable in that the Mehrangarh fort sits atop one such formation. And so does the park, sprawling across eroded hills and valleys of rhyolite, sprinkled with bits of welded tuff, another rock formed during the Malani event.

The park welcomes you with an assortment of rock sample exhibits, sourced from the western part of the subcontinent stretching from the Indus basin through the Thar desert to the Kachchh, with most from rock systems formed tens of millions years ago to more than a billion years ago. The most fascinating exhibit is a 635 million year old sample from the ‘Sonia Sandstone Formation’ near Jodhpur, containing ‘trace fossils’, which are traces of movements and burrows in the mud left behind by some of the earliest organisms which had no hard parts that could fossilize.

Just entering the arched stone gate where the ticket counter is located, one comes across an array of desert microhabitats that acts as a nursery for desert native plants. From that point on, a flight of stairs leads down to a 500 year old rainwater canal that channels water to the Ranisar and Padamsar lakes, some of Jodhpur’s oldest water reservoirs, located at the opposite end of the park. The canal, called the Hathi Nahar (elephant canal), which serves as one of the four trails earmarked in the park, cuts through a welded tuff formation, and soon meets a path that leads to the aforementioned lakes.

Another trail runs along the ancient city wall that also serves as a boundary wall for the park, and yet another trail meanders through the rewilded forest comprising more than 250 plant species. From most points of the park, one is treated to exhilarating views of the profile of the fort from various angles. My favorite location was from the edge of the Padamsar lake. Or was it from just below the foothills of the rhyolite hill on which the fort is located? I am confused.

An Unusual Safari

All this while, I had been debating with myself and my parents whether we should venture into a heritage or village style accommodation for the remaining night. Searching online, I had zeroed in on one candidate, Bishnoi Village Camp and Resort, located 30 km to the south of Jodhpur, somewhere in between Mogra Kalan and Kankani. Circumspect for the better part of the two preceding days, yet encouraged by many stellar recommendations of foreign tourists, we headed off to the resort.

And boy, were we bowled over by the host, who showered special attention on us, given that we were the only guests for that particular night. Following a late evening safari through the nearby villages, where we visited the workshops of craftsmen showcasing pottery, bedsheets and durries, we were treated to a most satiating and authentic Rajasthani meal, which included, among many things, bajra (millet) roti, kadhi, and the delectable Ker Sangri fortified with kumat.

The next morning was a revelation of sorts, when we set out for a 7AM early winter safari to see the elusive blackbuck and the migratory demoiselle crane, colloquially called kurja. Imagine the surprise when we learned that we had been staying in the same area where the infamous 1998 blackbuck hunting which had offended the Bishnois, had occurred .

The Bishnoi community, in deference to rules set down by their founding guru Jambheswar, protects wildlife and vegetation, sometimes, with their lives. Testament to this is the 1730 AD incident from nearby Khejarli village, where a Bishnoi woman, Amrita Devi along with her three daughters, gave up their lives protecting khejri trees from the felling attempts of the king’s soldiers, triggering a wave of such sacrifices in 82 other Bishnoi villages where tree-felling had commenced. With the final tally reportedly reaching 383, the king, eventually, had to ask for forgiveness and abort the tree-felling activity.

The blackbuck is even more sacred to the Bishnoi community, as Guru Jambheswar is purported to be reborn as a blackbuck. No wonder then that our safari included a stop at a memorial built by the Bishnois for the slain blackbuck. Then crossing the saline Luni river, the largest river of the Thar, and the only one that originates at Pushkar and ends in the Rann of Kachchh, we ventured into blackbuck territory. And lo and behold, in open spaces hidden behind curtains of bushes, we sighted a group of nearly 50.

However, as I learned, sighting blackbucks is not the challenge – it is just that the male blackbuck, which the layman has an image of in the form of a black upper body and white underbody, with long antlers, is rarer than the female blackbucks which have a brown upper body. Male blackbucks engage in lekking, whereby a single male takes control of a territory comprising multiple females and juveniles, driving away other males through aggressive means. It was interesting, however, to see two to three groups of blackbucks, led by their respective leading male blackbuck, mingling, while two male blackbucks at separate locations trudged through the forest, alone, in the distance.

With rapid urbanization, the wilderness available to species such as the blackbuck has rapidly shrunk. The forested area where we spotted the blackbucks, have, in fact, already been earmarked for future industrial development. It will not be long before the blackbuck population will be further impacted. Sadly, the convictions of the Bishnoi community can only do so much against this new advancing frontier.

Details for Visitors/Guests

Arna Jharna Museum

Entry fee: Rs. 100 per person

Visiting hours: 8:00 AM – 6:00 PM

The museum also conducts cultural folk programmes on occassion.

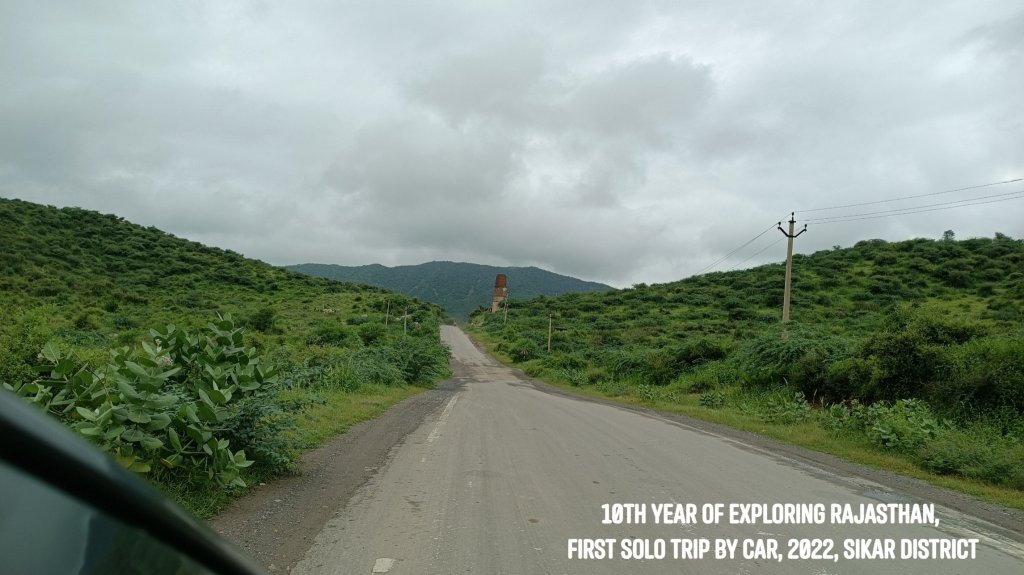

Drive from Jodhpur to the museum is remarkable.

Rao Jodha Desert Park

Entry fee: Rs. 100 per person

Visiting hours:

March to September: 6:30 am to 7 pm

October to February: 7:30 am to 6 pm

There are four trails, out of which three are in the area below the fort, i.e. the area which has been vigorously rewilded, and a fourth is around the Devkund lake, which lies adjacent to the Jaswant Thada, a short walk/drive away.

If time was a constraint, I would do the Yellow trail, to get a more involving flavour of the rewilding done in the park.

In warmer months, the trails are best done in the morning or evening.

Unsurprisingly, the park is at its beautiful best during the monsoons.

Keep an eye on their Instagram page to keep track of guided tours and other organized events.

Bishnoi Village and Camp Resort

Blackbuck and Village safari: Rs. 3000 for a group of 4-5 persons