That December day was going rather well. The weather had been very enabling, understanding, even – threatening now and then to pour, but holding back lest it should be branded spoilsport. Mother and Brother, both having agreed to an impromptu exploration of the Prachi Valley earlier that morning, appeared to be enjoying themselves too. There remained only one more temple to see. But it was now late afternoon, and before us, in echoes of Frost’s words, there lay two roads that diverged in the verdant coastland. One led to the temple, the other to Astaranga, literally, ‘of sunset colours’, a coastal town with an adjunct beach named Jahania.

Driving through the Prachi catchment area, we passed through hamlets and the occasional small town, interspersed among the lush paddy fields and the couple of rivulets and canals intersecting our path. Groups of coconut trees stood watch over betel-nut groves, and paddocks with haystacks, and roofs of the hut-like stalls and restaurants dotting the entries and the exits of the villages. Whenever the languorous clouds allowed, the sun would peer through the cracks, supplanted by the azure sky where the sun was absent.

The day had begun with the hope of making rendezvous with the eponymous river sometime in the afternoon, while trailing vestiges of heritage, as far as we could, along its course to the sea. My hastily assembled itinerary had ensured that we touched almost every pre-medieval temple worth seeing. There may have been a few tucked away in the interiors, and I may have been tempted, as is my wont, to veer off course, wading into uncharted territory. And yet that day I restrained myself – no adventure was worth scaring Mother and Brother so much that they dared not risk a trip with me in the future.

Stopping at several temples, defined by their intricately carved proud spires, built sometime between the 7th and 13th centuries AD, we had finally happened upon the mystical river, where our heightened anticipation had been met with a chastening modesty. Mother and I bemoaned how the current fate of the river coincided closely with the fortunes of our great land Kalinga which the copious waters must once have fed and drained, while Brother, who may or may not have agreed with our assessment, gazed unfazed at the coastal scenery outside.

With such topics dominating our conversation, we had reached the fork in the road. Between one more temple that would be another grim reminder of our diminished stature in the world, and a beach that could afford us a break from that grimness, the choice was easy to make. Thereon, my decision to not stop at Kakatpur – where the revered Mother Goddess Mangalaa is worshipped in yet another ancient temple – invited Mother’s ominous remonstration, “It is never good to invoke thoughts of visiting a Devi’s abode and giving it a deliberate miss.” Mother’s words resonated enough that I promised her we would stop on our way back.

Traversing a landscape taken increasingly over by larger clusters of coconut trees, and swathes of fishing ponds, we rolled downwards towards the sea on the Jahania road, flanked by trees and electric poles. Shortly, we found ourselves at the entrance to the beach, with the sun still high, and the threat of rain, having all but disappeared. Ahead stood a thicket of tall casuarina trees as if forming a curtain that when drawn aside would reveal a sight of the sea. Passing by the numerous make-shift stalls selling ice-cream, soft drinks, paan, snacks, hats and the like, underneath the shade of the casuarinas on hard land, we finally descended upon the nearly-white sands a few feet below, with the prospect writ large on our brow of seeing with our own eyes what the ‘sunset colours’ looked like.

Groups of people, old and young alike, frolicked on the beach. The ambience, however, reverberated with the jeers and profanities emanating from a particular group of college-going boys and girls. Mother remarked, “Such unruly youth these days!” Not contesting what she said, Brother led her up the coast where greater quietude was assured, and I followed suit. Mother dipped her feet in the approaching waters, observing the foot imprints left behind by the receding waters. Brother and I, reminiscing our childhood days, chased the springly water crabs that emerged from tiny pits in the sand and disappeared back into them when shadowed. Then, for moments in between, we stared at the steamers and the ships and the trawlers floating on the horizon, wondering what they were up to and what life felt like on them.

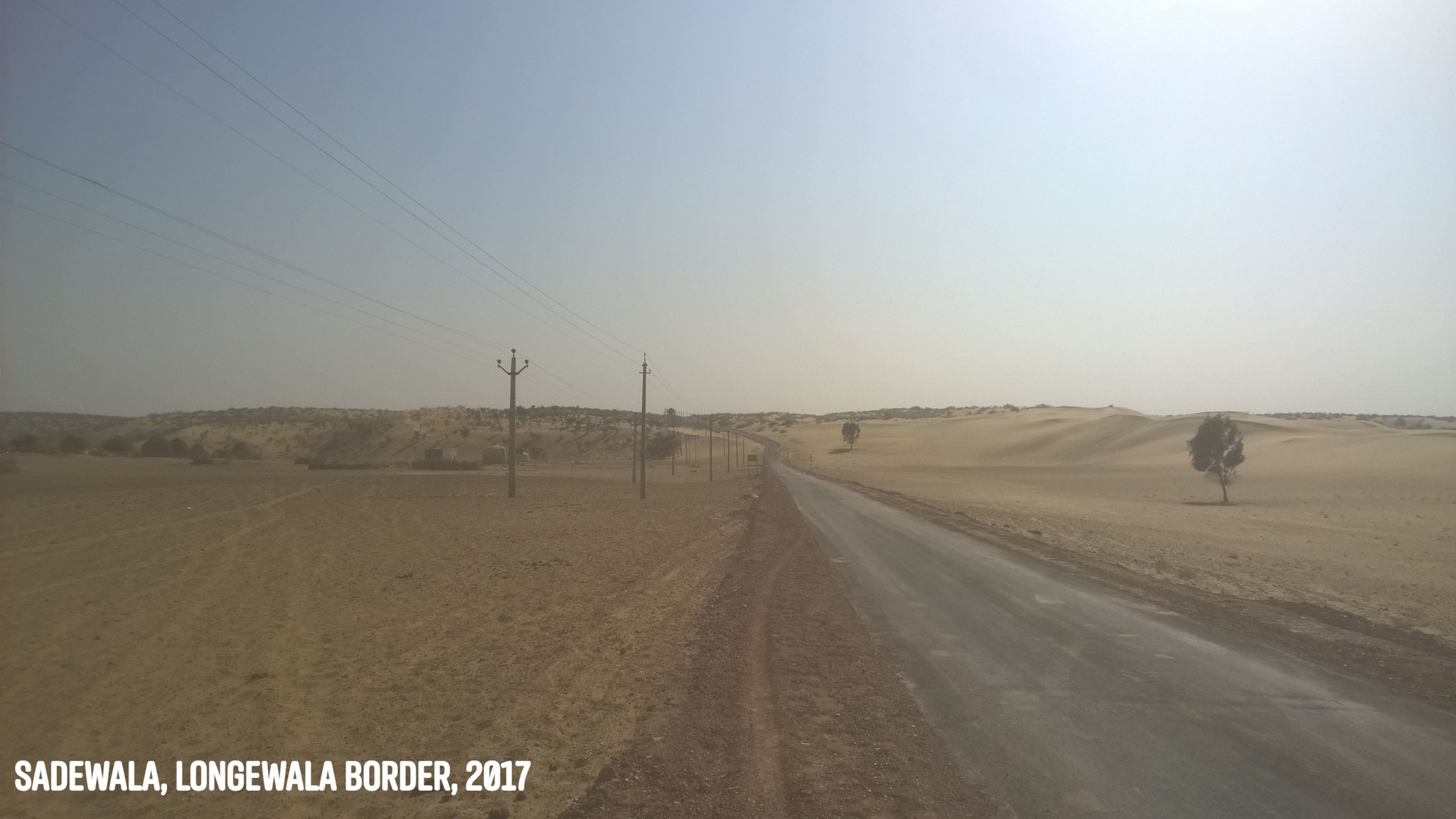

Even as Mother continued her therapeutic tryst with the playful waters, Brother and I turned our attention to the mini sand-dunes covered with thick shrubs lying towards higher ground but well in front of the column of casuarinas. Reminded of the dunes at Ranau in the Thar where we had visited earlier that month, we proceeded towards the dunes, hoping to relive some of the desert experience. Turning around a few minutes later, we caught Mother staring intently at the busier section of the beach, where the crowd had become more dense than when we had left it behind.

“Look at those kids hooting so hard – are those two having a competition or something?”, Mother said, pointing at a couple of figures bobbing up and down in the waters way off the coast. One of them was frantically waving both his hands. Brother furrowed his brow trying to infer the situation, and wondered, “Are these the same kids who were creating a ruckus?” Mother replied, “Yes, those trouble-makers.” The three of us stood ruminating over the sight in front of us, for about a minute, while the crowd seemed to be transfixed on those two seemingly competing figures.

“But why are those guys not approaching the beach, why are they moving away instead – is it a competition about who could go farther into the waters?”, I asked. Meanwhile, more people came down from the entrance to join the swelling crowd. One of the bobbing figures continued waving his hands. That is when it occurred to me, “Are those kids drowning?” Mother’s expression of disgust at the kids’ behaviour suddenly turned to one of panic, “Oh my god, baba, they are indeed drowning!” As if on cue, the swelling crowd seemed to stumble upon the same epiphany that we had just had, and immediately transformed into an island of commotion.

The three of us headed down nearer to the crowd, where the tension was now palpable. “They have been swept away, swept away!”, screamed a man, “Dheera bhai is trapped, save him, save him!”, shouted a girl, “Oh my god, oh my god, oh my god!”, wept another. The crowd moved like a shapeshifting amoeboid closer to the waters. Mother started hyperventilating, Brother looked helplessly at the scenes unfolding, while clasping Mother’s arm hard in a bid to soothe her. “But why is no one calling a lifeguard?”, I wondered aloud, “In fact, where is the lifeguard?”

The sun was now preparing to set, and the crowd had grown hysteric. It was clear the majority of the crowd comprised tourists, and the ones that were calmer were doubtlessly locals – they had seen too many such incidents before to be surprised. Nonetheless, neither the tourists, nor the locals seemed inclined towards any sort of samaritanism. And it got my blood to boil. I sprung to action, lamenting, “How on earth could people be this indifferent! Why is no one stepping forward to help?”

I sprinted up to the apparent locals, thundering, “Where is the lifeguard? Where is the lifeguard? What are we doing to save those guys?”

“Which lifeguard?”, quipped the cotton candy seller in Odia laced with a heavy local accent.

“The one who is supposed to save drowning people?”, I asked incredulously, as the din around me continued.

“Who cares about lifeguards here, sir?”, he replied, shrugging, with his trademark enunciation, “We have asked the police to look into it and they don’t take it seriously either.”

I was flabbergasted and inquired, “Still,there must be someone who does the saving when required?”

An old man standing behind the cotton candy seller interjected with a similarly accented Odia, “Tiyu is required!”

“Tiyu is the name?!”, I asked in confirmation. “Tiyu indeed.”, the man nodded.

So I slipped off my shoes and off I scampered away from the crowd of whom I had scant hopes, in the direction of the stalls at the beach entrance, screaming my lungs out, “Where’s Tiyu?! Where’s Tiyu?! Where’s Tiyu?!” On the way I encountered a couple of hefty middle-heighted young men with sinewy arms, running in the direction opposite to mine, towards the crowd, and I repeated, “Where’s Tiyu?” “If you have not found Tiyu yet on the beach, then Tiyu should be in one of those stalls.”, said one of them.

I shouldered on, overcoming the push-back from the sands below, with singular focus brought on by the adrenaline rush. I clambered up the incline leading to the stalls on the harder ground, and soon went about from stall to stall frenziedly crying, “Where’s Tiyu? Where’s Tiyu?” A stall keeper, seemingly the only one who had not deserted his stall for a glimpse of the action, replied, “I don’t know. If you have not found Tiyu yet on the beach, then Tiyu may be back at the town.”

I scanned the entire stretch of the stalls, but to no avail. Distraught at my inability to procure help for the poor kids back in the sea, I walked back heavy-footed towards the scene of action, dreading the knowledge of the outcome of the event taking place against the backdrop of the ‘sunset colours’.

As I approached the crowd, I noticed far out at sea four men flailing their arms and dragging a long cord at the end of which were tied two other men, while the crowd cheered them on with words of encouragement. The four men kept flailing on and on, drawing a few meters closer, then floating a few meters back, while slowly drifting laterally up the coast. The cheering crowd moved in lockstep, determined not to give up on the unheralded lifeguards. As the men drew closer, I realized two of them were the ones I had run into in my search of Tiyu. Before long, I had reunited with Mother and Brother who were now ensconced in the crowd.

After twenty minutes, seeming like an eternity, the ‘lifeguards’ along with the rescued boys were back on the beach. The rescuers walked off shaking the sand off their skin-hugging drenched clothes, even as the crowd thronged to the spot where the boys lay, in an apparent bid to chastise them for their foolish deeds. Still, an air of relief permeated the whole crowd. I spotted the two locals I had learnt of Tiyu from and approached them, grinning, “So Tiyu was not required after all?” “Why not? It did the saving, didn’t it?”, replied the old man in his typical accented Odia, pointing at the long thick brown-coloured plastic tube lying side-winded on the sand.

© 2020 Asiman Panda